If you were

taller than the tallest Husky (6-8),

If you were

taller than the tallest Husky (6-8),

you got in free!

|

As it celebrates its

50th anniversary, the NBA is tipping off the 1996-97

season with the New York Knicks against the Toronto

Raptors at Toronto's SkyDome. Toronto was also the site

of the league's very first game on Nov. 1, 1946, with

the Huskies hosting the New York Knickerbockers at Maple

Leaf Gardens. The contest drew 7,090, a good crowd

considering that virtually every youngster in Canada

grew up playing hockey and basketball was hardly a

well-known sport at the time.

Forget for now that the

game the Knicks won that night, 68-66, bore little

resemblance to the leaping, balletic version of today's

NBA. That game was from a different era of low-scoring

basketball, a time when hoops as a pro spectacle was

just coming out of the dance halls. Players did not

routinely double-pump or slam-dunk. The fact of the

matter was that the players did not and could not jump

very well. Nor was there a 24-second clock; teams had

unlimited time to shoot. The jump shot was a radical

notion, and those who took it defied the belief of many

coaches that nothing but trouble occurred when a player

left his feet for a shot.

The group of owners who

met on June 6, 1946, at the Hotel Commodore in New York

to talk about a league they would name the Basketball

Association of America couldn't have imagined today's

NBA. They were composed primarily of members of the

Arena Association of America, men who controlled the

arenas in the major United States cities. Their

experience was with hockey, ice shows, circuses and

rodeos. Except for Madison Square Garden's Ned Irish,

who popularized college doubleheaders in the 1930s and

1940s, they had little feeling for the game of

basketball.

But they were aware

that with World War II having recently ended, the

conversion to peacetime life meant many dollars were

waiting to be spent on products and entertainment. They

looked at the success of college basketball at Madison

Square Garden and in cities like Philadelphia and

Buffalo and felt a professional league, which could

continue to display college stars whose reputations were

just peaking when it was time to graduate, ought to

succeed.

So, on that Thursday in

June, 11 franchises were formed to compete in two

divisions. The East consisted of the Boston Celtics,

Philadelphia Warriors, Providence Steamrollers and

Washington Capitols, as well as New York and Toronto. In

the West were the Pittsburgh Ironmen, Chicago Stags,

Detroit Falcons, St. Louis Bombers and Cleveland Rebels.

Each team paid a

$10,000 franchise fee, the money going for league

operating expenses including a salary for Maurice

Podoloff, who like the arena owners who hired him was a

hockey man first. Podoloff, a New Haven, CT lawyer who

was President of the American Hockey League, agreed to

also take on the duties of President of the new

Basketball Association of America, which three seasons

later, in a merger with the midwest-based National

Basketball League, became the NBA.

With only five months

to get ready for the targeted Nov. 1 season opener, the

playing rules and style of operation were based as

closely as possible on the successful college game.

However, rather than play 40 minutes divided into two

halves, the BAA game was eight minutes longer and played

in four 12-minute quarters so as to bring an evening's

entertainment up to the two-hour period owners felt the

ticket buyers expected. Also, although zone defenses

were permitted in college play, it was agreed during

that first season that no zones be permitted, since they

tended to slow the game down.

Geography figured

heavily in the makeup of the 11 franchises. The

Providence Steamrollers relied heavily on former Rhode

Island College players, while Pittsburgh chose its squad

from within a 100-mile radius of the Steel City. The

Knick players came primarily from New York area

colleges. Even Neil Cohalan, the first Knick coach, was

plucked from Manhattan College. But all of Toronto's

players were American, with the exception of Hank

Biasatti, a forward, who was a native Canadian.

Salaries were modest, mostly around $5,000 for the

season. As a result, players had to rely on offseason

jobs for supplemental income.

By today's standards,

the first training camps were primitive, often a

day-to-day proposition. The Warriors, for instance,

shuttled between a number of Philadelphia-area

gymnasiums, usually on the condition that they scrimmage

the team whose home floor it was. This brought about the

curious spectacle one afternoon of a BAA team playing

against

A luxury was the Knicks'

outdoor court at the Nevele Country Club, a Catskills

resort in Ellenville, NY.

"The first two weeks we

were at the Nevele by ourselves," remembered Sonny

Hertzberg, the Knicks' first captain and a slick

two-handed set-shooter. "The meals were great, but the

coach wasn't satisfied. We did a lot of road work and

were in great condition but Cohalan didn't like the way

we were progressing.

"Looking back, I'm

still thrilled that I was at that first training camp

and that I signed with the Knicks. I wanted to play in

New York. It was a new major league. It was a game of

speed with no 24-second clock when we played. I didn't

know if it was going to be a full-time thing."

While the Knicks were

getting ready for the opener, college basketball was

still king in New York, where teams like CCNY, LIU and

NYU were revered. It was not until the Knicks scrimmaged

the collegians and the successes got some newspaper

notoriety that they started to gain some respect before

they left New York on Oct. 31 for the train ride to

Toronto.

Picture the scene that

cold autumn night when the Knicks had to stop for

customs and immigration inspection at the Canadian

border. The story goes that the customs inspector,

noting the physiques of Knick players like Ozzie

Schectman, Ralph Kaplowitz, Hertzberg, Nat Militzok and

Tommy Byrnes, asked, "What are you?"

"We're the New York

Knicks," said Cohalan, who did the talking for the team.

From the inspector's

reaction, it was evident that he had never heard of the

Knicks and probably not even of pro basketball. The

notion was strengthened when he added: "We're familiar

with the New York Rangers. Are you anything like that?"

Deflated but unyeilding,

Cohalan replied, "They play hockey, we play basketball."

Before letting them

through, the inspector added: "I don't imagine you'll

find many people up this way who'll understand your

game--or have an interest in it."

Little did he or the

players know that the NBA would grow into a

multi-million dollar business with 29 franchises,

including two in Canada (although the Huskies folded

after just one season).

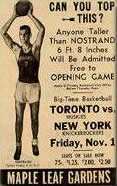

With the Maple Leafs'

image to contend with and only one Canadian player on

its roster, Toronto tried hard to promote the game. They

ran three-column newspaper ads bearing a photo of 6-8

George Nostrand, Toronto's tallest player, that asked,

"Can You Top This?" Any fan taller than Nostrand would

be granted free admission to the season opener; regular

tickets were priced from 75 cents to $2.50.

"It was interesting

playing before Canadians," recalled Hertzberg. "The fans

really didn't understand the game at first. To them, a

jump ball was like a face-off in hockey. But they

started to catch on and seemed to like the action."

Schectman, who starred

at LIU, scored the first basket of the game as the

Knicks jumped to a 6-0 lead. New York led 16-12 at the

quarter and widened the margin to 33-18 in the second

period before Ed Sadowski, Toronto's 6-5, 240-pound

player-coach, rallied his team to cut the gap to 37-29

at halftime. But Sadowski committed his fifth personal

foul three minutes into the second half and the rule

then, as it still is in the collegiate ranks, was that a

player fouled out on five fouls. The NBA limit was not

increased to six fouls until years later.

Nostrand replaced

Sadowski and put the Huskies ahead for the first time

44-43, and they expanded the margin to 48-44 after three

periods. The final quarter was ragged as well as rugged,

but a pair of field goals by Dick Murphy and a free

throw by Tommy Byrnes in the final 2 1/2 minutes

provided the Knicks with the two-point victory. Sadowski,

with 18 points, and New York's Leo Gottlieb, with 14,

led their respective teams.

During that first

regular season, the Washington Capitols, coached by Red

Auerbach, ran away with the Eastern Division

championship, finishing with a 49-11 record, 14

victories more than Philadelphia and 10 more than

Chicago, the West leader. However, it was the Warriors,

owned and coached by Eddie Gottlieb, who won the first

championship, beating Chicago 4-1 in the best-of-7 title

round.

Joe Fulks of

Philadelphia was the league's first scoring champion

with a 23.2 average, finishing far ahead of runner-up

Bob Feerick, 16.8. Feerick, however, was the league's

most accurate shooter, hitting .401 from the field--a

far cry from the .576 mark which Cedric Ceballos posted

to lead the league in 1992-93. |